Fall Army Worm Invasion and Control Practices

By P. M. Matova, C. N. Kamutando, C Magorokosho, D. Kutywayo, F. Gutsa, and M. Labuschagne

The following excerpts related to the Fall Army Worm (FAW) are taken from the paper Fall armyworm invasion, control practices, and resistance breeding in Sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA) written by Prince M. Matova, Casper N. Kamutando, Cosmos Magorokosho, Dumisani Kutywayo, Freeman Gutsa, and Maryke Labuschagne.

The fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda is currently the most damaging crop pest affecting maize in SSA. It is a polyphagous (feeds on several hosts) and migratory (can spread to other countries) pest that survives on at least 80 plant species, including maize, wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), sorghum [Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench], and rice (Oryza sativa L.). The consequences of FAW invasions on food and nutrition security have been made worse by lack of resistant/tolerant cultivars, poor capacity to control and manage the pest, and the suitability of the climatic conditions for the rapid multiplication and perpetuation of this pest. The fall armyworm, riding on migratory winds, has the potential to travel for long distances, and can prolifically breed in suitable environmental conditions typical of SSA.

Morphology and biology of fall armyworm

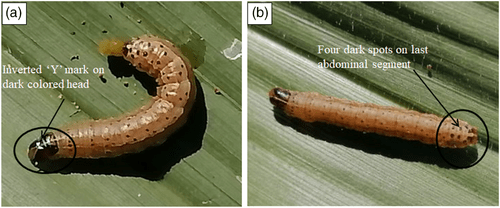

The Fall armyworm resembles both the African army worm [Mythimna unipuncta (Haworth)] and corn earworm [Helicoverpa zea (Boddie)]. However, the FAW has some distinct features that can help separate it from its close relatives, these include:

- a white‐coloured inverted “Y” mark on the front of the dark head,

(b) a brown head with dark honey‐combed markings (Figure a) and,

(c) four dark spots displayed in a square on top of the eighth abdominal segment, as shown in Figure b.

Figure 1- Physical appearance of the fall armyworm (FAW) larvae highlighting the most distinguishing features of the worm.

FAW infestation signs and symptoms

Typical early FAW infestation signs and symptoms include small “pin holes” and “window panes” (Figure 2a), resulting from feeding of the small worms on leaves (Figure 2b). Damage of maize plants caused by FAW attack is severe during the late pre‐tassel stage (Figure 2c). Bigger larvae consume large amounts of tissue and do much more damage compared to small larvae, resulting in a ragged appearance of the leaves (Figure 2d). It is also important to appreciate that foliar damage on maize may look serious but may not necessarily translate into high grain yield losses, as reported by a study carried out by the U.S. Department of Agriculture ‐ Agricultural Research Service (USDA‐ARS), in which they noted that FAW defoliation as high as 70% at 12‐leaf stage could cause just about 15% grain yield loss. Fall armyworm defoliation on maize rarely goes above 50%.

FIGURE 2

(a) Fall armyworm (FAW) egg masses and first signs of FAW infestation on leaves.

(b) Young FAW larvae (black heads) emerging from egg masses on window pane damaged leaves.

(c) Advanced FAW damage, showing dead heart on the growing point.

(d) Large FAW larvae protected by ‘frass plug’ while feeding in the whorl during tasselling stage.

Reproduction and multiplication rates

The FAW’s rate of reproduction and multiplication is rapid; coupled with the fact that FAW does not have a diapause (the biological resting period), it can establish as an endemic pest. For instance, one adult female moth is capable of laying between 1,000−2,000 eggs during its lifetime. Eggs are laid in egg masses of between 100−200 eggs. In warmer climates, the duration of the egg stage is only 2−3 days. The larval stage lasts between 14 and 30 days in warmer summer and cooler winter months, respectively. Whereas the lifespan of an adult moth is approximately 10 days. The pest is able to complete its life cycle in 30 days at an average daily temperature of 28 °C. This implies that in warm climates, such as those experienced in SSA, FAW can have multiple generations in one season.

Fall Armyworm control strategies

Currently, researchers are working on immediate and long‐term solutions to the problem. Breeders are developing cultivars that can offer native resistance to the pest, while chemical companies, entomologists, and other researchers are developing insecticides, bio‐controls, and cultural‐methods, respectively, to minimize crop damage that can result after infestation.

- Synthetic and botanical pesticide control practices

As an emergency response strategy to FAW invasion in 2016, most governments in Africa distributed chemical insecticides to farmers through extension. Some of the broad‐spectrum pesticides that were being used included Thionex [Endosulfan 50%], Carbaryl [Carbaryl 85WP], Dimethoate [Dimethoate 40EC], and Karate [Lambda cyhalothrin 5EC].

These were later replaced by more efficient and eco‐friendly pesticides, which included Ecoterex [Deltamethrin (C22H19Br2NO3) and Pirimiphos methyl (C11H20N3O3PS)], Emamectin benzoate (4′′‐Deoxy‐4′′‐epi‐methylamino‐avermectin B1)/Macten (Emamectin benzoate 5%), Super dash [Emamectin benzoate and Acetamiprid [N‐(6‐Chloro‐3‐pyridylmethyl)‐N′‐cyano‐acetamidine)], Ampligo [Chlorantraniliprole (3‐Bromo‐4′‐chloro‐1‐(3‐chloro‐2‐pyridyl)‐2′‐methyl‐6′‐(methylcarbamoyl)pyrazole‐5‐carboxanilide, 3‐Bromo‐N‐[4‐chloro‐2‐methyl‐6‐[(methylamino) carbonyl]phenyl]‐1‐(3‐chloro‐2‐pyridinyl)‐1H‐pyrazole‐5‐carboxamide, DPX E2Y45) and Lambda‐cyhalothrin (C23H19ClF3NO3)], and Belt [Flubendiamide (N2‐[1,1‐Dimethyl‐2‐(methylsulfonyl)ethyl]‐3‐iodo‐N1‐{2‐methyl‐4‐[1,2,2,2‐tetrafluoro‐1‐(trifluoromethyl) ethyl]phenyl}‐1,2‐benzenedicarboxamide)].

- Cultural agronomic practices

Different cultural practices that have been utilized across SSA in managing and controlling FAW infestation and maize yield losses include, handpicking and killing of larvae, placing sand or wood‐ash in whorls of maize plants, drenching plants with tobacco extracts, deep ploughing to kill overwintering pupae, early planting, destruction of ratoon host plants, burning infested crop residues after harvesting, intercropping with non‐host plants, use of multiple cultivars, and rotation with non‐host crop

- Biological control practices

Studies show that Push and Pull Technology (PPT) based on intercropping maize with greenleaf desmodium [Desmodium intortum (Mill.) Urb.] and bordering the intercrop with Brachiaria ‘Mulato II’ is effective in FAW control. The Desmodium protects the maize by emitting semiochemicals that repel (push) the moths that are concurrently attracted (pulled) by semiochemicals released by the border crop. ICIPE (2018) and Midega et al. (2018) reported that FAW infestation can be reduced by at least 80% in a field where the technology is being practiced.

- Host plant resistance strategy

Access to cultivars with some level of resistance or tolerance to FAW brings cost‐effective control to the resource‐poor smallholder farmers in SSA. Native resistance is defined as resistance that is naturally available in the gene pool, harnessed through selection for effective use in agricultural production systems. Native resistance offers minimal but significant protection to a crop, but it is usually combined with other management measures in an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategy.

- Integrated pest management strategies

The FAW IPM strategies are targeted at preventing or avoiding pest infestations, and management of established infestations. This involves routine scouting to identify and respond to infestations, to suppress the pest using the IPM triangle strategies, that is, minimum application of safe pesticides, provision of safe, scientifically proven or evidence‐based options to farmers, and managing insect resistance to pesticides. The IPM triangle is a practice that enhances effective application of IPM strategies by considering control as a three‐pronged strategy comprising of chemical, biological, and cultural control, all based on effective pest monitoring.

For full academic references and citations of the article, please refer to Irwin Goldman, Introduction to the special Crop Science issue: Celebrating the International Year of Plant Health, Crop Science, 10.1002/csc2.20342, 60, 6, (2841-2842), (2020). Wiley Online Library

Images provided by Stanley Gokoma and Prince M. Matova